Exhibitions's texts

C - The Time of Reciprocal Responsibilities

We women and men, the sovereign people of Ecuador […] hereby decide to build a new form of public coexistence, in diversity and in harmony with nature, to achieve the good way of living, the sumak kawsay. (Constitution of Ecuador, 2008, Preamble)

Indigenous Peoples’ cultures and practices are based on the maintenance of good relations with the different elements making up the ecosystem and on the sustainable development of resources. Humans and non-humans, which may be animals, plants, mountains or spirits, have reciprocal responsibilities and follow negotiated standards of behaviour. In this relational perspective, mountains, rivers or salmon are animate. Indigenous Peoples often speak of their responsibility to protect natural resources for future generations. This commitment with regard to nature is fundamental for Indigenous Peoples’ cultures, values and identity. The principle of responsible management of natural resources which they defend is increasingly reflected in global action in favour of the environment.

The Prince Kidnapped by The Salmon

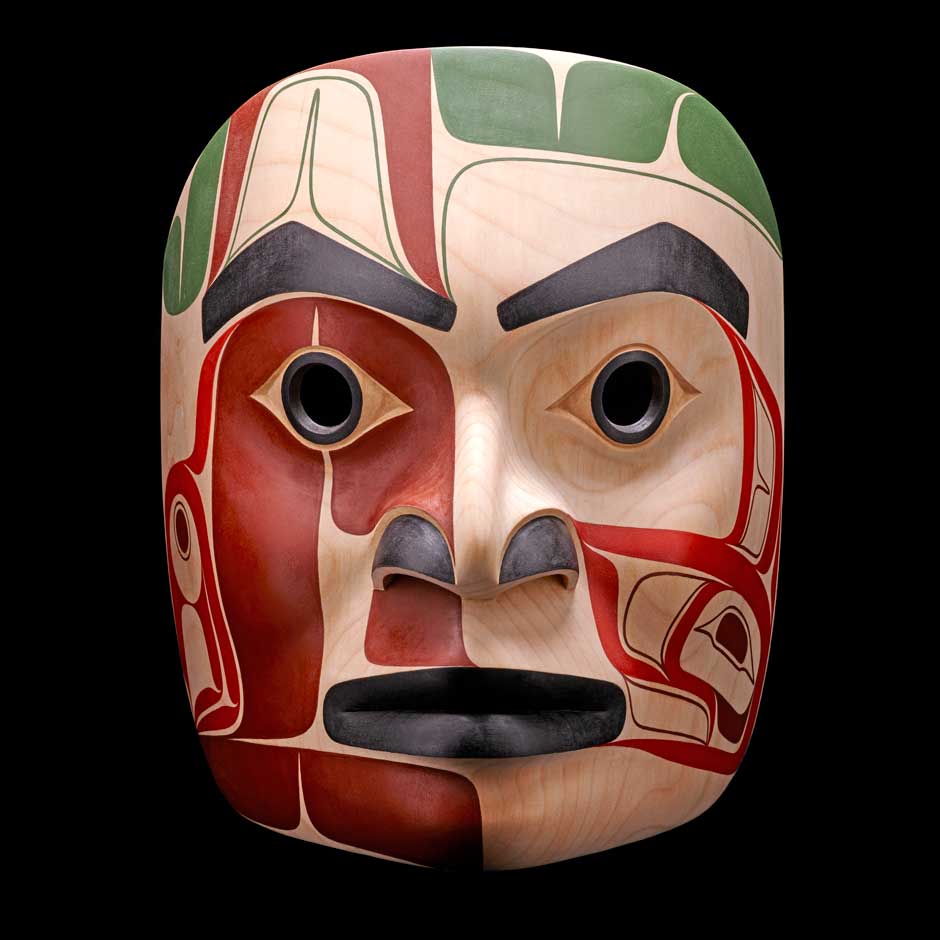

Amiilgm Smgan Cedar Mask

By Gyibaawm Laxha - David R. Boxley (1981-)

Ts'msyen

United States, Alaska, Metlakatla

2020

Alder wood, acrylic paint

Made for the exhibition

MEG Inv. ETHAM 068759

© MEG, J. Watts

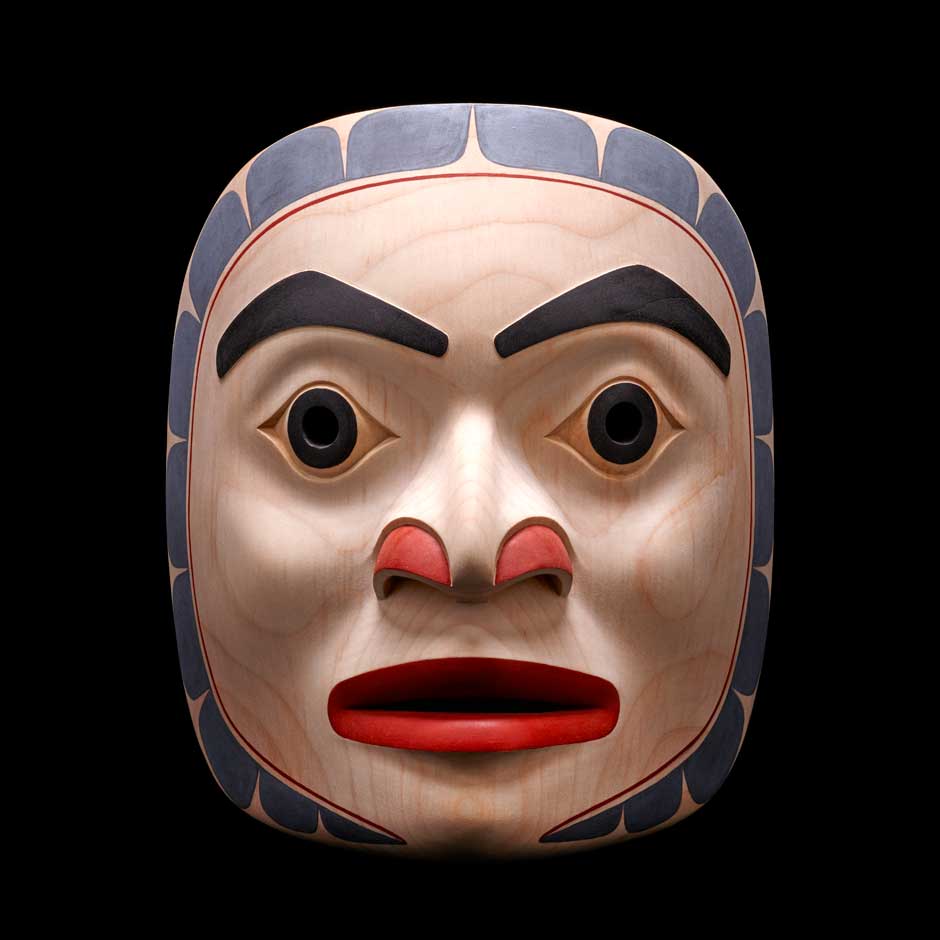

Amiilgm Łguwaalksik Prince Mask

By Gyibaawm Laxha - David R. Boxley (1981-)

Ts'msyen

United States, Alaska, Metlakatla

2020

Alder wood, acrylic paint

Made for the exhibition

MEG Inv. ETHAM 068760

© MEG, J. Watts

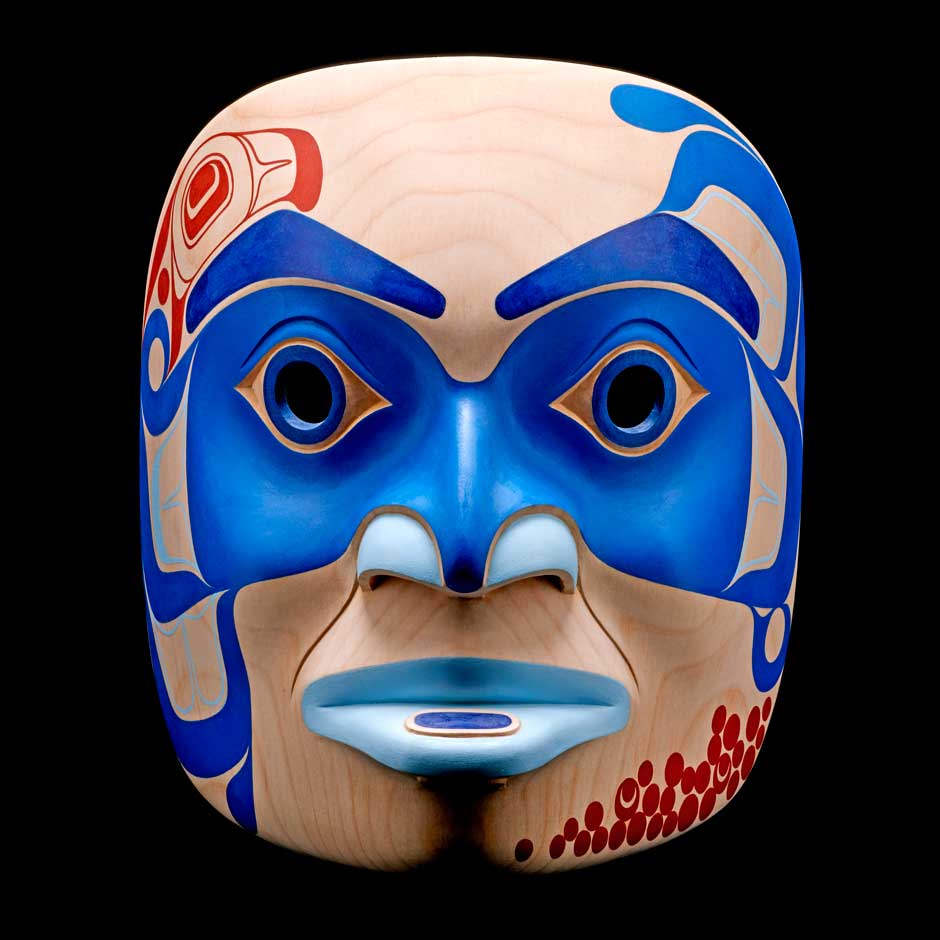

Amiilgm Ḵ'ala Aks River Mask

By Gyibaawm Laxha - David R. Boxley (1981-)

Ts'msyen

United States, Alaska, Metlakatla

2020

Alder wood, acrylic paint

Made for the exhibition

MEG Inv. ETHAM 068761

© MEG, J. Watts

Amiilgm Sm'ooygidm Hoon Salmon Chief Mask

By Gyibaawm Laxha - David R. Boxley (1981-)

Ts'msyen

United States, Alaska, Metlakatla

2020

Alder wood, acrylic paint

Made for the exhibition

MEG Inv. ETHAM 068762

© MEG, J. Watts

In 2017, rainfall in south-east Alaska was the lowest in forty years. The flow of rivers decreased and the rise in their temperature affected the salmons’ survival. That year, the town of Metlakatla published a plan for adaptation to climate change and identified salmon as a vulnerable priority. Salmon are a key species for the Indigenous People of Alaska. They form the basis of the inhabitants’ commercial and cultural activities. They begin and end their lives in freshwater and feed in saltwater, which makes them very sensitive to environmental changes. The Prince Kidnapped by the Salmon is a Ts’msyen short story reinterpreted by the poet Gavin Hudson with the collaboration of the sculptor David R. Boxley. Four voices evoke the Ts’msyen’s relationship with the Salmon people and remind us of our responsibility towards natural resources.

Artist’s statement - Huk Tgini’itsga Xsgyiik/Gavin Hudson, Ts’msyen, Metlakatla, Alaska, original version

“The indigenous worldview is one of interconnectedness, sustainability, and balance. It offers a way forward in this time of chaos, crisis, and desperation. The Ts’msyen philosophy of Sag̱ayt K’üülm G̱ood, (All of One Heart), expresses unity through love and universal consciousness. It could not be more clear that the global climate emergency, wars, poverty, famine, species extinctions, and the impending water shortages are all symptoms of a break from Sag̱ayt K’üülm G̱ood. We cannot live without the salmon, the cedar, the river, nor the sea. These are all woven together in one super system. If one is destroyed then all others will follow. But when we live in oneness, in harmony with nature, following the rhythm of Mother Earth’s heartbeat, we transcend the traumas and illusions of separateness imposed by colonization. Perhaps our artforms may be a reminder of the important role human stewardship plays in the unfolding destiny of our world.”

Huk Tgini’itsga Xsgyiik - Gavin Hudson

Artist’s statement - Gyibaawm Laxha / David Robert Boxley, Ts'msyen, Metlakatla, Alaska, original version

The Ts'msyen have understood since time immemorial that there is a human spirit inside all living things, that humans are not separate from the natural world, but merely a part of it. This inextricable connection between humans and the world around us is a reminder of our responsibilities to care for it all. We inherited this knowledge from our elders and we must embody their wisdom and impart it to our descendants. Too many of us have ignored these lessons for too long, and unless humanity crawls out from under the colonial mindset and free our hearts to act with courage and love, our own self-destructive actions will consume the whole world. We have the power to save Mother Earth and with it, ourselves. I hope my work will help you to remember the salmon will only return if we are respectful and the earth will only allow us to stay if we live in balance with it. 'Ni'nii wila loo łagigyedm ada 'ni'nii sgüü dm waalm (That is what the ancestors did and that is what we should do).

Gyibaawm Laxha - David Robert Boxley

From Creation Narratives to the Right to Live in a Clean Environment

In the perspectives of many Indigenous Peoples, the relationship with the earth and natural resources is inseparable from spirituality and the creation narratives recalling the agreements made with non-humans. This relationship is strengthened by the learning and handing down of knowledge from one generation to another as well as by Indigenous Peoples’ involvement in the protection of their fundamental rights. Indigenous Peoples’ demands for the protection of their territories and ecosystems have been taken to court thanks to the development of legal means. In Ecuador, Bolivia and New Zealand, for example, Indigenous activism has helped to create a veritable legal phenomenon which broadens the concept of human rights by adding to it relations with the environment. This new legal framework entails increased recognition of the collective right to live in a clean, healthy and sustainable environment.

Living Well on and with the Earth

The principles of reciprocal responsibilities between humans and non-humans are central to the Indigenous way of life. Their origin lies in creation narratives and their perpetuation depends on the fight for the preservation of the capacity to live well on Earth with all forms of life, a principle present for example among the Anishinaabe people in North America. The notion of living well or Sumak Kawsay in the Quechua language has been listed in the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia since 2008 and 2009. It is claimed by many other Indigenous Peoples. Everyday objects, artistic creations and songs recall the nurturing cosmogonic narratives, such as the creation of the Anishinaabe world by Nanabozo or the origin of the Shuar world by Aurtam and Nunkuit.

Indigenous Australian Paintings: from Dreamtime to Territorial Rights

For the Indigenous Australians, all features of the landscape, water holes, rocks, dunes, islands and constellations, are considered to be marks of the ancestral beings’ actions during the Dreamtime. Since 1976, with the promulgation of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, the federal government has recognized the Indigenous Australians’ right to claim unoccupied Crown land, on condition they can prove their connection with the territory in question. Artists take part in legal claims by painting their group’s narratives. The paintings are used as cadastral evidence in special courts dealing with land claims. The act of painting thus reinforces the Indigenous Australians’ heritage rights to their territory.

Learning to Negotiate with N0N-Humans in Inuit Territory

Many Indigenous Peoples have close relationships with animals and plants. According to some traditions, relations with animal entities rely on the negotiation of agreements. Humans and their non-human partners all have rights and responsibilities so as to preserve their agreement in the long term. The repeated negotiation of these agreements ensures peaceful coexistence based on respect and mutual benefit. This interdependence between human and non-human entities is carefully maintained in order to preserve lasting peace and healthy relations. Inuit stories enable us to understand these reciprocal responsibilities. Some of them bear witness to acceptable, encouraged forms of behaviour while others depict unacceptable forms which in the end lead to a break in the relations between humans and non-humans and thus threaten humans’ future.